Starting this month, I’m going to be regular contributor to A Deeper Story, a writing collective that has been dear to my heart from Day 1. I had the unexpected and just plain awesome opportunity to sit down and chat with ADS founder Nish Weiseth this summer (over panini and gelato in Tuscany, no less!), and our conversation turned toward Don Miller’s book Blue Like Jazz . Perhaps you’ve read it too, especially if you were one of the many hungering for “Nonreligious Thoughts on Christian Spirituality” in the early 2000s. It was a liberating book for me—engaging where most Christian books were preachy, thought-provoking where others tended to push agenda-laced answers—and Nish pointed out that the reason Blue Like Jazz was so compelling was that it framed theological discussion inside of story. No Bible-thumping. No argument-baiting. No dry platitudes or impersonal formulas. Just one person’s unique and intriguing experience with faith.

. Perhaps you’ve read it too, especially if you were one of the many hungering for “Nonreligious Thoughts on Christian Spirituality” in the early 2000s. It was a liberating book for me—engaging where most Christian books were preachy, thought-provoking where others tended to push agenda-laced answers—and Nish pointed out that the reason Blue Like Jazz was so compelling was that it framed theological discussion inside of story. No Bible-thumping. No argument-baiting. No dry platitudes or impersonal formulas. Just one person’s unique and intriguing experience with faith.

That’s what A Deeper Story is as well: a place where Christian spirituality is explored through the writers’ own experiences. It’s beautiful and relatable and surprising and mind-stretching, and I highly recommend poking around the site for a bit after you read my piece. You’ll see why it’s a community I’m delighted to call my own.

Now on to the story…

[Ed: Now that Deeper Story has closed its doors, the post is here in its entirety:]

~~~

“Between two lungs it was released

The breath that carried me

The sigh that blew me forward”

– Florence Welch

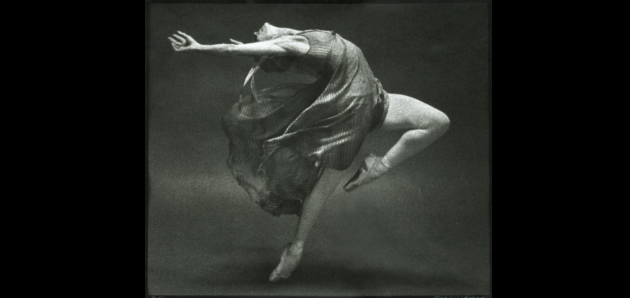

At eleven years old, I had no notion of a drill sergeant except for what I’d seen in a passing clip of Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C., but I was pretty sure my ballet teacher fit the bill. As my class labored over our barre exercises, she paced the ranks, snapping commands like rubber bands into the smalls of our backs.

“Chest out! Head up! Stomach flat! Tuck that seat in! Breathe up and down, not in and out! No one wants to see your diaphragm move! Turn that leg out! ROUND ELBOWS, for the love! Stand tall, everyone! Taller!”

I adored my teacher despite her Sergeant Carter routine, and I practiced my posture daily at home. A real ballerina was a whipcord, long and lithe and compressed within an inch of her life. A real ballerina could corset herself through willpower alone. I cinched my ribcage tight in the mirror and watched each breath push my non-existent bosom upwards.

Perfect. As close to perfect as I was going to get, at any rate.

There it was in the mirror for God and so great a cloud of witnesses to see: the successful suppression of self. There was the proof that for all my excesses and deficiencies, all my shameful impulses and sins of omission, I could at least hold my respiratory system in check. I could breathe without breathing, and if I could do that, surely I could learn to pray without ceasing and do all things without grumbling and go a whole blessed hour without incurring the wrath of a Father who was perfect as I was not.

Forget Sergeant Carter; God was the greatest caricature of a short fuse that I knew.

///

Four years ago, my husband coaxed me out to the running trail below our house with promises of cardiac health and cute workout clothes. Our younger daughter had just started preschool, so my fallback excuse of “Sorry, got these two kids” (à la Jack Handey) wasn’t going to fly anymore. Besides, my fondness for that excuse was doing me no favors in the waistline department. Full of good intentions and the merry optimism of the ignorant, I laced up my running shoes and hit the track with my husband.

Two minutes later, I was hobbling at the speed of an asphyxiated snail, purple-faced and gasping for breath. It was one of the sexier moments in our marriage for sure. Dan jogged in placed beside me while I wheezed out my list of reasons why exercise is detrimental to one’s health and marital happiness, punctuating every sentence with an “OW.” I suggested he go ahead and put me on hospice care because I clearly wasn’t going to make it.

He suggested I try breathing.

When we made it home later that morning (no small miracle), I consulted Dr. Google about why running made me feel like my sides were being surgically removed with sporks, and I discovered that Dan had been on to something. Breathing was the secret, the Internet explained. Specifically, belly breathing. By keeping the air high and tight in my chest, I was putting stress on my diaphragm and depriving my muscles of oxygen. Instead, I needed to be relaxing my torso, filling my lungs to capacity, and then letting all the air out in an easy whoosh. If I did this, the Internet promised, my body would stop the gutted gastropod routine.

So I tried it. The next day at the running trail, I flopped my arms around to loosen myself up and then took a deep bellyful of breath. Immediately, air rushed into my lungs, whistling down dusty tubes and rousting cobwebs from long-forgotten bronchioles. I could feel it inside me, a blustering brightness that expanded until I thought I might float away. My stomach hadn’t ballooned so freely since the last time a baby had been in residence. (“Suck it,” I thought in the direction of passing runners with their hardwood abs and lack of pregnancy symptoms. “I’m learning to breathe here!”)

Exhaling was next, a conscious release of the breath I’d just taken in. I hadn’t realized that this would be the harder step, but instinct clenched itself around every precious molecule of air and had to be pried away one finger at a time. Ridiculous as it sounds, I had to whisper to myself that another breath would be waiting for me after I let this one go. I hadn’t used up all the air in our great green park. I could trust that no matter how far I ran or how extravagantly I spent each lungful, there would be enough left. There would always and forever be enough.

///

I don’t know what I’d expected from that first exercise in belly breathing, but it certainly wasn’t a total spiritual overhaul. You can’t learn “the unforced rhythms of grace” in one area of life, see, without it affecting all the others, and once I learned to breathe deep, I couldn’t stop.

I began to inhale truth about the destructive religion of my childhood and to exhale story. I let myself drink brimful from the kindness in Jesus’s voice and sigh from satisfaction instead of angst. Before my eyes, the God who had always been breathing down my neck faded away, a pernicious mirage, until I could finally see the God who breathes life into clay lungs, the one whose breath had been carrying me all along. “So spacious is he,” writes Paul, and I stopped right there on the page, unwilling to read on until those words had inked themselves onto my soul.

So spacious is he.

I hadn’t known.

Everything comes down to breathing for me now. Whether I’m running or praying or wrestling with doctrine or opening a blank page, the secret is in relaxing whatever I’ve got clenched—all my righteous restraints and illusions of control—and trusting that I can fill and release and be filled again. I think of it as a kind of life Lamaze, this focused refusal to hoard tension. Just like the hilarious “hoo-hoo-hee-hee” panting techniques I had to practice in childbirth class, it goes against my instincts. I feel unstable without my old fear and shame and exclusion-based doctrines to clutch, and the risk of taking each moment by faith unsettles me further.

Being able to relax in the company of God, however, is a gift worth every existential discomfort. So spacious is he that my lungs can’t fill beyond his capacity to provide. So spacious is he that I can travel from one set of perspectives to their opposites without losing his trail. So spacious is he that my days of corseting myself and standing ramrod straight at the barre are over; now it’s our time to run.

“Gone are the days of begging

The days of theft

No more gasping for a breath

The air has filled me head to toe

And I can see the ground far below”

image credit

was released into the wild today, and this makes me glad for humanity. It’s her gift of sacred unconventionality put to paper (or, uh, Paperwhite), and I don’t imagine that many of us who pick it up are going to be the same when we put it back down. At the very least, we’ll be several pounds lighter in exhaled cynicism.