When I began this blog back in 2007, I in no way intended to write about my spiritual life. In fact, I intended not to. Marching into the depths of my topsy-turvy faith with a notepad was a prospect so scary that I rarely even attempted it in the privacy of my own company. I planned to blog about parenthood and living overseas and maybe, occasionally, the quirks in my personality, but not spirituality. Never spirituality.

As you might have noticed, that resolution has held up about as well as a toilet paper kite in a thunderstorm.

It hasn’t gotten any less scary for me to write about my evolving relationship with God, just so you know. Blogging requires significantly more pep talking and espresso than I originally conceived, and I go into full-blown vulnerability hangover mode at least once a month. The freedom to share what’s going on behind the scenes of my heart, though, is worth every bit of discombobulation (as is the opportunity to use words like “discombobulation”), and I’m honored to the depths of my quirky soul that you’re here to read this.

Today I’m confessing to a new bit of unorthodoxy over at A Deeper Story, where I’ll join you once I’ve issued myself another pep talk or two. You bring the coffee?

[Ed: Now that Deeper Story has closed its doors, the post is here in its entirety:]

~~~

“Sometimes, when people ask me about my prayer life, I describe hanging laundry on the line… This is good work, this prayer. This is good prayer, this work.”

– Barbara Brown Taylor

Rarely do I call on God’s intervening powers more fervently than when someone looks around the circle and asks, “Whose turn is it to pray?”

Mine. It’s almost certainly mine. In fact, I’ve been shirking my pray-aloud duties for so many years that I probably owe the Christian community about 3,708,000 consecutive blessings at this point.

The Bible study leader or head of the holiday table knows this and looks straight at me, but I have retreated into my one and only evasive maneuver: the Preemptive Head Bow. I close my eyes and fix my face in a half-smile as if I’m already agreeing in spirit with whoever is chosen to pray. NOT ME. God, for all the love you bear me and my remaining scraps of soul dignity, make them choose NOT ME.

It usually works. Most people are reluctant to call on someone who looks to be already busy communing with God. Every now and then though… “Bethany, we haven’t heard from you in a while!” I then whisper to God the most honest expression of my soul in that moment, which is Dammit.

It’s not that I don’t know what to do in this setting. I grew up a worship leader’s kid in a Southern Baptist church. I know how to pray aloud, from the first “Father God” to the final “in your name we pray,” and I can still whip out a passable blessing under social duress. The problem is that every word of a proper prayer feels like a stumbling block in my throat. The corners rasp against my lips even as I will myself to sound ardent, bad acting made all the worse by my complicity in it.

No one has ever pointed out that my prayers tend to come out like strangulated haikus—Dear God thank you please / something on togetherness / in your name amen—but I still project my unease onto those listening. I imagine them getting together later to compare notes and plan some kind of spiritual intervention for She-Who-Tries-To-Avoid-Praying. I wouldn’t blame them either. After all, what kind of Christian doesn’t want to talk to God? That’s like being the kind of chef who refuses to touch food, or the kind of Red Sox fan who just shrugs when the Yankees win.

Something fundamental is clearly missing. At least, that’s what I used to think.

I kept an uneasy truce with prayer—accepting it as a necessary discomfort, a kind of religious underwire—until my college years. Like many students, I found the gift of unknowing in lecture halls. My professors challenged me to question and research, to unclench my perspective so I could learn. And I determined I would. I marched myself into Mardel Christian Books one Texas-bright morning and left with a stack of prayer guides as deep as my desperation. This collection of expert theology, surely, would activate my latent prayer gene.

If you’ve ever read more than two Christian how-to books in your life, you already know how the next part of this story goes. Prayer is an exercise in blind persistence, the first book told me. No, no, no–prayer is a magic spell, said the second. If you have enough faith, God will give you your own prayer language, insisted the third. Yo knuckleheads, stop bothering God with all this talking business and just listen, countered the fourth.

I’m simplifying, of course, but the whole thing felt far from simple as I abandoned book after book in frustration. Prayer was supposed to be the baseline of any Christian’s relationship with God, but I couldn’t even do it in the privacy of my own mind. I couldn’t come up with words that rang true for me, much less ones that would transport me to the park bench where God was waiting to chat. And forget about a personal prayer language. I knew five-year-olds who could speak in tongues, but God was obviously not wasting that gift on me. It was just my voice, stammering in plain old Christianese, and the answering silence.

I never felt further from God than when I tried talking to him.

So finally, several years and several hundred arid please-and-thank-yous later, I just stopped. I stopped trying to untangle the telephone cord between God and me. I stopped forcing words into the blank space between us. I stopped pretending, at least to myself, that I was the kind of person who could start a meaningful conversation with “Dear Father in heaven.” I wasn’t. I didn’t know how to be, though God knows I’d tried. For whatever the reason (was I not sincere enough? did my soul come with a manufacturer’s defect? did God just straight-up not care?), prayer had never worked for me, and I was done trying to act like it did.

And there, in the dusty aftermath of doctrine, is where we had our first heart-to-heart.

I was in the kitchen reaching for something in my baking cabinet when an impulse swept down into my arms, a sweet, warm rush that brought my fingers to life before my brain quite realized what was happening. I knew, without knowing, that I was making brownies to take to my neighbor suffering from homesickness. More than that, I knew that I wasn’t alone.

For the next fifteen minutes, I sifted cocoa and flour, whirled sugar into butter, and greased baking pans, and every motion was a prayer. I could feel my neighbor’s struggle like a heavy and precious weight against my ribs and God as the lifeblood pulsing between it and the whisk in my hands. Not a single conscious word interrupted our rhythm. Our care, mine and God’s, went into every stir of that brownie batter, and I sensed the full truth of Jesus’s words: “At the moment of being ‘care-full’, you find yourselves cared for.”

My body was the spiritual conduit that my mind had long failed to find.

These days, I still pray best through baking. Mixing up carb-loaded comfort is my liturgy and taste-testing my sacrament. Hold your eye rolls for one second while I tell you that the secret ingredient is love. (And butter. But mostly love.) This isn’t the only way I’ve found to interact with God though. We communicate when I photograph mountain wildflowers, when I lie back to watch the stars, when I cuddle my sleepy daughters, and even when I go running—each physically emotive act expressing my soul better than words ever did. I’ve come to realize that this kind of physical-emotional intentionality is my personal prayer language, the completely unconventional way that God has chosen to connect with me.

I still haven’t figured out how to explain to Bible study leaders that I only pray with my body, sorry. People tend to think I should be more orthodox as it is. One of the most wonderful surprises of my adult life, however, is that God always meets me in my unorthodoxy. When my wounded heart can’t bear a certain interpretation of the Bible any longer, God meets me outside denominational lines with a new perspective. When who-I-am fails, once again, to fit religiously sanctioned roles, God affirms my identity, the unique image of [her]self that I have to offer the world. When I admit that I can’t talk to God, he gives me a prayer language that doesn’t require words. That he would meet me in the wilds of my baking cabinet, far from the park benches of conventionality and the rhetoric of experts, says more to me about his love than a by-the-book spirituality ever could.

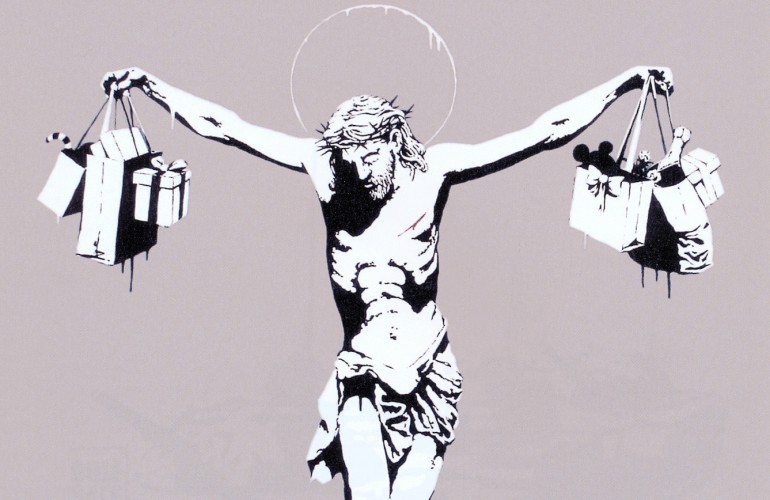

image credit

was released into the wild today, and this makes me glad for humanity. It’s her gift of sacred unconventionality put to paper (or, uh, Paperwhite), and I don’t imagine that many of us who pick it up are going to be the same when we put it back down. At the very least, we’ll be several pounds lighter in exhaled cynicism.