Growing up Quiverfull, I was always aware that we had more to prove than ordinary families did. When we attracted public stares, whether for being out on a school morning or simply for the novelty of so many stair-step children at the salad bar, my siblings and I took our cue to behave as much like miniature, meek adults as possible. I, as the oldest of eight, took this especially to heart. When relatives brought up concerns over my parents’ choice to homeschool, I knew that my grades were our first line of defense. When various adults from church took me aside and told me I could talk to them about anything, I said thank you and clamped my mouth tight around my smile.

Our lifestyle was hard to defend, which made defending it all the more essential to us.

The truth is that we adopted fundamentalist ideologies like patriarchy, authoritarian parenting, and legalism out of fear, not because they bettered our lives. We believed thunder-voiced leaders who told us that isolation from the world was the only way to save our souls. God’s wrath was a specter shadowing every aspect of our daily life from what we ate to how childish energy should be managed, and when we suffered, it was for our own failure to measure up. Telling onlookers the truth was never an option.

Instead, we took up offense as our best defense.

We proclaimed that public-schoolers were idiots with inferior educations as we hid the fact that one of my siblings struggled with learning disabilities that only got worse through horrific at-home “treatments.”

We loudly judged the physical and emotional closeness we saw in couples who were dating (as opposed to family-chaperoned “courting”) while we buried shameful secrets about what can happen in a family when the males are given authority over the females’ bodies.

We declared that children were not safe around homosexuals or social workers or atheists or Democrats even as my siblings and I wore extra clothes to cover the bruises we had sustained in our own home.

I was used as an example of how successful the Quiverfull movement was in producing superior future leaders who would take back the United States for God, though I was told in private that I had no potential and no character, that I was stupid and regrettable and damned.

It’s clear to me in retrospect that promoting our lifestyle was a strategy to deflect attention away from our dysfunction. Mind you, I’m not sure that it worked. My husband points out that having adults continually offer me a listening ear wasn’t normal; many people in our church and neighborhood must have sensed that our home life was much less idyllic than we pretended. However, our loyalty to our beliefs was our shield, and if we had been offered a reality television show from which to champion our choices, I believe we would have taken it.

Yes, this is about the Duggar scandal. It’s about why I was so utterly unsurprised last week when news broke that Josh Duggar has a history of sexually preying on young girls including several of his sisters. While the circumstances of our childhoods were not identical, the ideologies behind them were, and I know firsthand how quickly evil can incubate in an isolated and repressive environment.

It’s no coincidence that Bill Gothard, founder of the Institute in Basic Life Principles whose lifestyle teachings heavily influenced both my family and the Duggars, was ousted from his organization last year after thirty-four accusations of sexual abuse by women who worked for him. Nor is it mere chance that Doug Phillips, founder of another Christian organization that widely promoted patriarchy, homeschooling, and other common tenants of the Quiverfull lifestyle, has had his life unravel over the last year after news of his infidelity and a sexual abuse lawsuit by his children’s former nanny. Despite how adamantly these two men spoke out against worldliness and impropriety during their careers, their positions of “God-sanctioned” power gave them the perfect opportunity to act on their impulses. Perhaps it’s even why they spoke so adamantly.

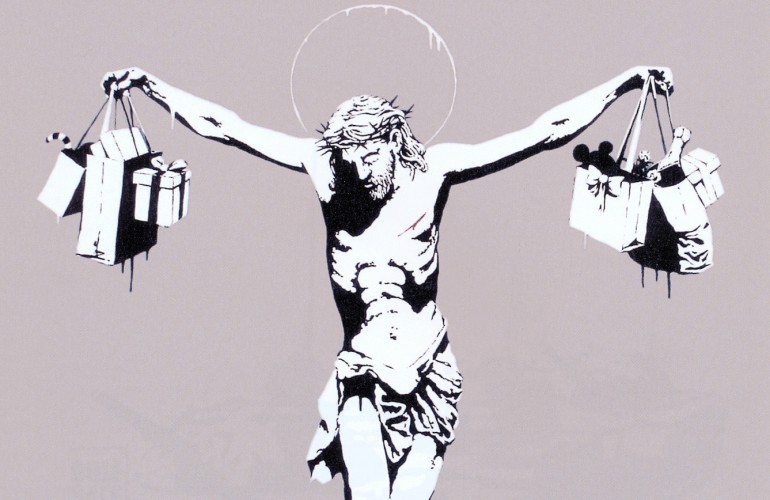

The best defense is a good offense, and how can you better divert attention from your own sexual behavior than to preach against others’? How can you further distance yourself from a history of child molestation than to take a job publicly implying that LGBT individuals are a threat to children? How can you cover up the sexual abuse perpetrated on and by your children any more thoroughly than to publicize yourselves as the model Christian family? “The lady doth protest too much” may not apply to every situation, but Shakespeare was a better judge of human character than most.

My point is that none of us should be surprised by the news of Josh Duggar’s crimes or his parents’ attempts to cover them up. The system of beliefs under which he and I both grew up creates an environment in which the powerful can inflict abuse with few repercussions, their victims can be made to feel responsible, and defending the family lifestyle is more important than helping the family heal. Growing up Quiverfull taught me to hide family secrets through misdirection, offering up my ultra-modest wardrobe and political rants and Bible memorization trophies to public scrutiny so that no one would guess the horrors happening behind the scenes. Last week’s news is just another reminder that I was not alone in this.

As sickening as the Duggar scandal is to hear, I’m hopeful that its exposure will offer a counterpoint to the façade of a happy, healthy family that they’ve televised over the last six and a half years. The cocktail of movements I call Quiverfull for lack of a more comprehensive term is nothing to be admired. Rather, it is a control-based system that allows—and sometimes encourages—different forms of abuse while publicly touting itself as God’s ideal, and the more people who recognize this in the wake of current news, the more understanding and support we will be able to offer its victims.